- Home

- Wainwright, Robert

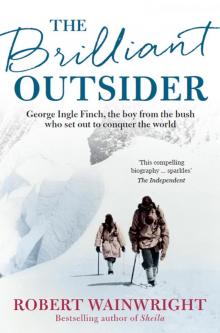

The Brilliant Outsider

The Brilliant Outsider Read online

DEDICATION

To my wonderful sons,

Stevie and Seamus

CONTENTS

Dedication

Part I

1. To See the World

2. A Boy from Down Under

3. A New Hemisphere

4. Whymper’s Path

5. A Zest for Mountains

6. Everest Dreaming

7. King of His Domain

8. The Tyro Companion

Part II

9. An Alchemy of Air

10. The Upstart

11. A Jilted Hero

12. Pleasure and Pain

13. The Last Frontier

14. The Lost Boy

15. ‘You’ve Sent Me to Heaven’

16. ‘Dear Miss Johnston’

17. The Threshold of Endeavour

Part III

18. Prospects of Success

19. The Politics of Oxygen

20. ‘When George Finch Starts to Gas’

21. The Road to Kampa Dzong

22. Goddess Mother of the World

23. The Foot of Everest

24. The Right Spirit

25. A Bladder and a T-Tube

26. The Ceiling of the World

27. ‘My Utter Best. If Only . . .’

Part IV

28. The Unlikeliest of Heroes

29. The Bastardy of Arthur Hinks

30. A Dream is Dashed

31. The Tragedy of George Mallory

32. A New Legacy

33. The Beilby Layer

34. F Division and the J-Bomb

35. ‘Whose Son Am I?’

36. Conquered

37. Recognition at Last

Epilogue

Acknowledgements and Notes on Sources

Index

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

PART I

1.

TO SEE THE WORLD

George urged his pony up the steep slope. He could feel the animal’s laboured breath beneath him, its flanks glistening with sweat as they pushed higher and higher, through the stands of crouching snow gums and silver-leafed candle barks that clung to the side of the long-extinct volcano.

The boy would remember the morning that would come to define his life as dewy. It was early October in 1901, one calendar month into spring, and the Australian bush around the inland New South Wales town of Orange – higher, wetter and cooler than the land to the west or the east – was still thawing from the winter, the mornings dark and frosty.

He had been up for hours, riding out from the family property to hunt for wallaby before the sun crested the surrounding ranges to melt the overnight frost and wash the countryside in pale gold. He might have woken his younger brother, Max, but had thought better of it, preferring to be alone in the waking bush with the utter sense of freedom that it brought.

Tall, lean and physically mature beyond his thirteen years, George had skirted the sleeping town and headed for Mount Canobolas, the highest inland point of the tablelands, a dozen or so miles to the south-west, where he was confident he would find the kangaroo-like marsupial feeding in mobs as the day warmed.

He and Max had hunted in the lower reaches of Canobolas many times before, but had never been interested in venturing up the towering rise, let alone pondering the origins of its name, a rather loose attempt at replicating the local Aboriginal word meaning a twin-headed beast.

They would come here to hunt, skinning and stretching the pelts of the animals they shot so they could be sold to dealers for four-pence each, and then using the money to buy fresh ammunition. But it wasn’t the financial reward that drew George, who once sewed his mother a blanket from the six wallaby hides of a successful hunt. The money was simply a means to an end for a boy from a well-off family who relished the challenge and strategy of the hunt itself.

On this day George had found the wallabies easily enough – a mob of them at a waterhole in the virgin bush. He had waited, patient and content in the silence, for an opportunity, but when it came the flash of his gun barrel in the morning sun had stirred the animals and they’d scattered into the trees. Instead of following and perhaps scaring them further, George had decided to get to higher ground so he could spy where they had settled and try again.

There had never been a reason to climb even the lower reaches of Canobolas, and its freshness was intoxicating. The air was cooler up there as the mountain continued to shed the remains of its white winter coat. Small patches of snow still weighed down the boughs of some trees, ready to fall, melt and pool in the rock gullies where it would feed the flush of an Australian spring already evident in tiny flowers of kunzea, fringe myrtle and mirbelia that would soon explode into a blaze of white, yellow, red and violet.

It was mid morning when George reached a point high enough to be able to spot the wallabies again but he did not stop, instead choosing to keep going, the hunt all but forgotten as he sought the peak. One challenge had been replaced by another.

When it got too steep he searched for alternative routes where his pony, sturdy and sure-footed, could tread. At last he broke free of the dense foliage and reached a vast rocky outcrop that tapered into a stepped chimney to the summit, a series of upright rectangular blocks of stone that might have been placed there by a giant hand. His mount could go no further but, eager to continue, George dismounted and scrambled to the top in a few minutes, barely raising a sweat – then stood transfixed at the sight before him.

He hadn’t stopped to consider what he might see from the summit or how his perspective of the world might change simply by viewing it from above. His eyes roamed across the scene in front of him, unable to pause even for a moment, such was the surreal nature of the view. Olive-green fingers of bushland reached out from Canobolas as if trying to claw back the plains of yellowed farmland that spread toward the Great Dividing Range, its rolling curves layered in hues of brown, blue and purple as they stretched to the horizon.

When he lowered his eyes and squinted into the still-rising sun, George could make out the glinting galvanised-iron rooftops and whitewashed walls of the houses of Orange, positioned in neat rows beside wide dirt roads crafted like ruled pencil lines, which led, ultimately, to the jewelled city of Sydney, 150 miles to the east. Years later he would recall the moment as clearly as if he was still standing there: ‘The picture was beautiful; precise and accurate as the work of a draughtsman’s pen, but fuller of meaning than any map. For the first time in my life the true significance of geography began to dawn upon me, and with the dawning was born a resolution that was to colour and widen my whole life.’

George remained atop Mount Canobolas for what seemed like hours, eventually tearing his eyes from the view and reluctantly climbing back down the stone steps to retrieve his pony. The boy would return home empty-handed several hours later but it mattered little, the spoils of a hunt replaced by a vision of his future: ‘I had made up my mind to see the world; to see it from above, from the tops of mountains whence I could get that wide and comprehensive view which is denied to those who observe things from their own plane.’

George Finch, a boy who until then had only seen his world from the height of a saddle, wanted to be a mountaineer.

2.

A BOY FROM DOWN UNDER

Early in the summer of 1891, a few months after his son had turned three, Charles Edward Finch picked up the boy, dangled his legs over the side of a small wooden dinghy and plopped him into the calm, crystal waters of Sydney Harbour with the simple instruction, ‘Swim, George, swim.’

The boy would do as he was told, fighting his way back to the surface and furiously dog-paddling to the gunwale, where he was plucked to sa

fety by those same strong hands. George Finch would tell the story many times over the years, always fondly, dismissing any outrage among the listeners by arguing that his father had acted not out of cruelty but love, believing that in order to survive and thrive his son had to learn early to take care of himself.

The legacy of self-reliance that Charles Finch wanted to pass on to his children was not surprising given his heritage. His father, a redcoat soldier named Charles Wray Finch, the son of a far from prosperous clergyman, had arrived in Sydney aboard the convict ship Hercules in 1830 after a harrowing five months at sea. Once in New South Wales he was quickly promoted to the rank of captain, although he was not interested in a military career, and when the opportunity arose he resigned his commission to take up an appointment as a police magistrate. It was the beginning of a social and economic climb that would eventually make him one of the most prominent men of the colony, and his prospects were boosted by his marriage to Elizabeth Wilson, eldest daughter of the colony’s powerful police magistrate, Henry Croasdaile Wilson.

The Finches soon quit Sydney and helped lead the push inland from the main colony, accepting Crown grants to develop the fertile agricultural and pasture land west of the Dividing Range. It was on a sheep station in the Wellington Valley that Finch called Nubrygyn Run (based on an Aboriginal phrase meaning the meeting of two creeks) that he not only made his fortune but, with Elizabeth, raised a family of nine children.

The station, running more than 12,000 sheep and 800 cattle, was a lush, blooming oasis in an otherwise harsh landscape, its homestead a sprawling stone building with seven bedrooms for family members and guests and large drawing and dining rooms for entertaining, leading onto a broad timber verandah with views across tended lawns to a creek that fed the paddocks. There were extensive vegetable gardens and an orchard with grapevines and over three hundred trees – peaches, cherries, apples, pears, plums, nectarines and apricots among them.

The gardener lived in a stone cottage, as did the station overseer, and there were separate quarters for household staff and the twenty-five farmhands, stockmen and shearers needed to run the operation. At the back of the house stood the stables and horse paddocks, to the side a massive brick woolshed with a 30-foot shearing floor and boasting the only hydraulic wool press in the district.

Charles Wray Finch would live at Nubrygyn for fifteen years before selling part of the property and securing a manager to run the large parcel of land that remained. He took his large family and fortune – ‘estates of several thousand acres in extent in the county of Wellington and house, cottages and town allotments at Parramatta’ – and settled back in Sydney where he was welcomed into business and political circles, becoming a founding member of the Australian Club, joining the committee of the Royal Agricultural Society and being elected to the New South Wales Parliament. He was the parliamentary sergeant-at-arms, keeping order in the House, when he died suddenly in May 1873.

Charles Edward was his third child and second-oldest son, brought into the world in the main bedroom of Nubrygyn in 1843 and spending the first dozen years of his life on the station, until he was sent off to the King’s School in Parramatta, making the journey on the back of a bullock wagon hauling wool bales to the city. Although he was ingrained with life on the land, the family’s move to Sydney in 1855 shifted his expectations from the hardy life of a farmer to a privileged city existence and career. He graduated from high school with good grades, but surprisingly chose to bypass a university education in favour of a position with the New South Wales public service as a draughtsman. With diligence, and aided by the standing of his father, Charles worked his way through the ranks to become a district surveyor.

In 1885 Charles Finch would return to the Wellington Valley when he was appointed chairman of the Land Board at Orange, presiding over disputes concerning the Crown Lands Act, the guiding document in the division of New South Wales’s vast tracts of arable land. In this role he would become more powerful than his father in many ways. He was a physically imposing man, tall and square-jawed, his neatly trimmed white beard contrasting with his dark, prominent eyebrows. His manner complemented his physical appearance: regarded as an uncompromising but fair man, he was a stickler for the rules and famous for once successfully defending a decision before the Privy Council in London, for which he earned the nickname ‘King’.

Charles had never quite lost touch with his farming background. As the oldest surviving son (his elder brother had died in a farming accident), he inherited Nubrygyn when his father died and assumed the role of gentleman farmer, adhering to the strictures of Victorian morality and fashion, and donning formal dress for dinner, even in the heat of an Australian summer. He had married in 1870, aged twenty-seven and well set in his career, 21-year-old Alice Sydney Wood, the only daughter of a prominent family in a ceremony presided over by the Lord Bishop of Sydney. The marriage was widely reported in colony newspapers, as was Alice’s sudden death just a year later, most probably in childbirth.

The loss of his young wife seemed to traumatise Charles because he remained widowed for the next sixteen years. He was finally married again in 1887, two years after moving back to Nubrygyn, this time to nineteen-year-old Laura Isobel Black, a woman twenty-five years his junior, who quickly bore him three children before he turned fifty.

George was the oldest, born on August 4, 1888, as Sydney celebrated the centenary of the First Fleet’s arrival, while the rest of the populace, scattered across the vast southern land, grappled with the notion of a unified nation rather than a collection of independent states. By the time George Finch climbed Mount Canobolas on his pony thirteen years later, the Federation of Australia had been created, sparking the beginnings of a national identity that would be tested and refined by a world war that would soon devastate the fledgling nation with the loss of more than 60,000 lives.

Learning to swim was not the only lesson he received from his father, as George would recount in the last years of his life on a few pages of handwritten memories, the pencilled words fading on yellowed paper found lying at the bottom of a suitcase filled with his personal files. Titled ‘The Boy from Down Under and his Adventures and Life’, it is a statement not only of the significant early influences on what would be an extraordinary journey, but of his clear sense of identity as an Australian, even at the end of a life that took him to the other side of the world.

As much as Charles Finch expected his children to play responsible and productive roles in life, he also wanted them to leave their own mark, which might not necessarily align with his own, on the world. As George reminisced: ‘Our father taught us from our earliest years to love the open spaces of the earth, encouraged us to seek adventure and provided the wherewithal for us to enjoy the quest and, above all, looked to us to fight our own battles and rely on our own resources.’

Some lessons were admonishments for stupidity – pointing an unloaded gun at a friend’s head or attempting to lure out a deadly black snake sleeping beneath the floorboards of his bedroom with a bowl of milk. More profound were the encouragements to explore the natural environment, from the virgin land beyond the boundaries of their rural homestead to the waters of Sydney Harbour where George and Max and their sister, Dorothy, spent summer holidays in the bay below the house their grandfather had built at Greenwich Point, swimming behind shark-proof nets and sailing dinghies across the harbour to the chimney-topped city in the distance.

At its peak in the middle of the nineteenth century, Nubrygyn boasted a schoolroom, general store, blacksmith’s shop and a hotel which the bushranger Ben Hall and his gang once held up, spending a night of merriment on stolen liquor in front of bemused residents. But by the early 1890s, when George was ready to start school, the village cemetery with its handful of gravestones was all that was left besides the still-grand homestead and its prosperous acreage.

The nearest large town was Orange, the birthplace of Banjo Paterson and named incongruously after the King of the Netherlands, form

erly the Prince of Orange. George made the twenty-mile round trip each day on his pony to Wolaroi Grammar School, rewarding his steed with Tasmanian apples, but struggling himself to concentrate on the tedious formulated lessons. It was an eternal frustration for his parents who could sense a promising intellect behind the poor grades.

Things were different out of the classroom where George was a natural on a horse – ‘dropped in a saddle at birth’, as his father put it. He and Max were taught how to break and care for horses – they were to be curry-combed gently, brushed, fed and watered before the rider looked after himself, because ‘a good horse is never to be treated as a machine but always as the rider’s best friend’. They were expected to help muster cattle and sheep and ride the boundary fences to repair wires, strung low and tight to keep out the hordes of rabbits that ranged across south-east Australia threatening to destroy threadbare pastures.

George took his father at his word and explored the country every chance he got, often returning late at night and once riding as far as the Blue Mountains, falling asleep in the saddle on the return journey and relying on his horse to deliver him safely to the homestead as dawn broke the next morning.

He quickly became a crack shot with his .410 shotgun, practising on anything that was deemed a pest, from snakes to dingoes, and establishing a flourishing trade in pelts. The brothers even panned for gold in the streams around Mount Canobolas, once finding enough colour and small nuggets to buy new saddles and bridles.

George’s love of adventure also extended to the water, not just the summer expeditions sailing dinghies back and forth across Sydney Harbour, but the romance of the open ocean. As an eleven-year-old he was riveted by newspaper accounts of a North Sea confrontation between the pride of the British navy, the battleship Revenge, and her Russian counterpart, the Czar. During an earlier summer he clambered aboard the famous wool clipper Cutty Sark as she lay at Circular Quay and, much to his mother’s chagrin, asked for a job as a cabin boy. Despite her forbidding it, he sneaked aboard the next day and was given a trial, clambering easily into the rigging but upending a pot of tar – carried aloft by deckhands to coat the ropes and make them waterproof – which smashed onto the polished deck and ended his chance of a life on the high seas.

The Brilliant Outsider

The Brilliant Outsider